Print Collectors Information

This guide contains thoughts on all manner of things pertinent to printmaking – from editions & print publishers to Contract Printers - all the odd & obscure shop talk & confabulations having to do with our peculiar practice of the ‘’Black Arts’.

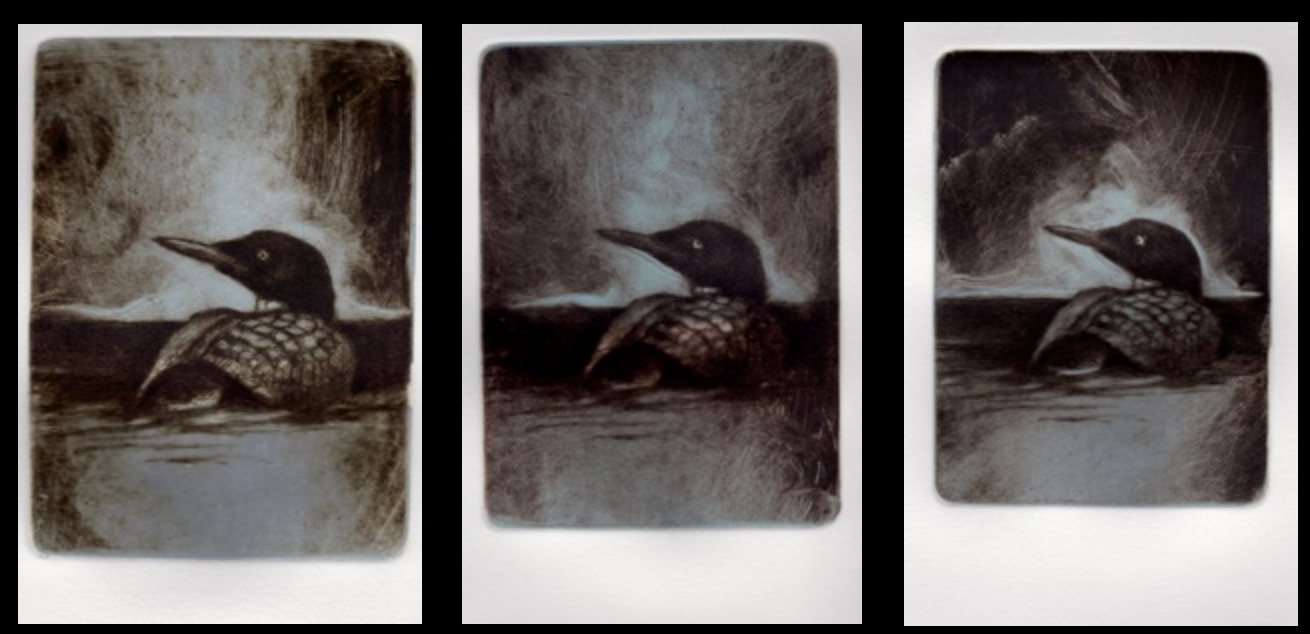

Here above are two impressions from the same Kingfisher plate seen in the display of waterbirds. It’s an older plate that has seen some use and even gradual abrasion of the drypoint (the more velvety line-work that is scratched in with a diamond point rather than done with acid). The earlier impression is on the right. From the recently pulled impression to your left a discerning and experienced observer/collector might detect that some of the rough edges of the drypoint burr are now showing signs of wear. That problem can generally be overcome with a little more care in wiping and printing of the plate and most of us printmakers will at this point go back into a plate and freshen the drypoint a bit anyway. Most of you will have heard of drypoint and know you should be looking for this and yet be a bit fuzzy on what all this insider talk is really about. Fear not, though, for I have met many a curator and museum director who could use a refresher course and who is grateful for a little shop talk and some hands-on ‘show me’. You are not idiots and neither do I know all there is to know about other art media. I am to this very day not so crystal clear in my own mind on the subtleties of salt firing and raku. Yet my own wife’s preferred medium is ceramic sculpture.

Drypoint is occasionally a way to do a whole plate - ala prima - without acids or a lot of intervening technology. Just you and a diamond point needle, drawing into a polished gleaming sheet of copper - lightly dancing across that pristine surface, barely touching here and digging in there. It may be hard to control and yet oh-so rewarding when the dance happens just right. Here the quality of that drawn modulated line is essential. Usually drypoint is just a part of the whole etching - a certain delicate passage here or there and most often a way we juice up certain passages and get more ink to stay in places we want to see develop a truly deeply lusciously velvety black - indeed that coveted thick viscous polychromatic black with cold undertones and warm overtones and well - we do go on, don’t we?

The drawn diamond point line, unlike the flat and relatively uniform etched line, has a uniquely velvety lusciousness valued by artist and collector alike. Imagine a plow going through the spring earth and throwing up a moist furrow of soil and that is microscopically a good approximation of what is happening. The plowed furrow, is uneven, unpredictable, rough, unstable – but from an aerial photo it would take on a certain uniformity. Take a turn with the needle as you’re gouging out a drypointed line – dig deeper into the turn and the point throws up a furrow more to the outside of the turn than inside, corresponding to the newly changing angle of your hand. That furrowing or raising of a burr of displaced copper is hardly a tidy, easily repeated or tightly controllable matter. It is ragged and uneven under a microscope and undercut in several directions and like the soil of a spring plowing, unstable. You rub ink into it and get ink under the burr and around it and it starts to crumble and abrade in small ways. You wipe it with a rag (or cheesecloth-like ‘tarlatan’) to remove redundant ink in preparation for printing and the ink piles up on both sides of that burr, but the burr itself gets caught on strands of the cloth as microscopic pulling and tearing happens and more breakdown of the burr inevitably occurs. Run it through a press to get the impression and that pressure will over time begin to flatten the burr down so it will begin to hold ever so minuscule amounts of ink less with the next inking and pressing and then the next time just a bit less once again and so on - until there comes a point when it seems a palid diminished shadow of what it once was - hard to say what exactly is wrong - but less juicy maybe.

Burr ain’t all the same and not even always good. The artists view of a burr is that we want to achieve an effect and sometimes too much burr bothers us and we knock it down some or partway through an edition you see it weakening and so you go into the plate and gouge it a bit and raise some more burr - get the print to hold just a bit more ink in some crucial passage. We can do that on our own plates, but imagine that a professional printer is doing this work and there’s a publisher involved (like the famous Vollard Suite - or a Tamarind printer). They can’t make those decisions for the artist and they don’t want a discussion to ensue among collectors as to which part of the edition is from the original drypoint and when it got worse and from which number up they’d fixed it again and ultimately which numbers are the good ones worth purchasing and conversely, which are not.

Artists with well-established reputations, who know they can sell large editions, will typically have their printing done by a contract printer. Every print is then identical to the extent that’s humanly possible. They will ensure that this so in order to keep customers happy that there is no diminution in quality throughout the edition. It is, however all based in pecuniary rather than aesthetic decisions. Many will even have their plates plated in the harder but also more brittle metals; nickel, chrome or steel – to sustain far longer runs. It may be a good financial investment if the market will bear long runs of their work, but they have also closed the door to making any changes in the plate.

Like most artists lacking a good crystal ball and a mass audience, I do not know which impression will sell well and require my keeping a drawer well-filled with these hot little money-makers. I also do not know when the muse will wake me up in the middle of the night with intimations that I am fooling nobody with that incomplete and half-hearted attempt at an etching I am fobbing off on the public and that it needs work. I thus leave the editions open and do not chrome-face my plates. Instead I keep them about my studio and hope they don’t get damaged, falling back on the parsimonious Solomon’s solution of just taking more impressions as I actually need them. And sometimes they get into my grasping claws during those moments of doubt and find a completely new and hopefully improved form - destroyed or improved as the case may be. And the impression you bought will have been quite unmistakably done before or after that impulsive and irrevocable watershed moment.

Variability within these editions can, as you now plainly see, be quite substantial. That is, however, not something that overly concerns me, nor should you be that concerned either. They aren’t necessarily better or worse - just not all the same - not an industrially made product. The work of hand carries its marks of honor. Variability too is a part of that equation. That said, you might like one impression better than another and that too is a part of the delight in visiting the studio and seeing it all up close – becoming more involved in the process.

I could make notes on how I made my inks and what papers I used or keep a final comparison proof at hand as does any contract printer. Artist themselves though, have no rules or requirements and need not meet the demands of a paymaster and his expectations. We can make our work however we want and then change our minds; mend plates, add some imagery, throw in some remarques around the edges, freshen the drypoint - make the image over into a whole new print - whatever creative mania the muses send us chasing off after..... It isn’t a game and there are no rules. Art has meaning and is beautiful or powerful – or it doesn’t make the grade and no amount of cleaving to any arbitrary playbook will save it.

From this one example and then the one below, you will clearly see that how one applies ink and mixes it with varnishes and how one wipes the plate results in markedly different image qualities. Papers aren’t all the same and even ambient humidity and atmospheric conditions affect print quality. I find that only gradually, with time, do I learn how best to print a plate - that it doesn’t come to me all at once and that l tend to prefer later impressions when I have had some time to live with the plate and evolve the printing itself. Of course among print collectors there is the mystique of the drypoint burr and a delicate spit bite. Early impressions tend to be the most valued, when the evanescent and fugitive qualities of these ephemeral techniques are still unquestionably incorrupt. Some believe in the established reputations of contract printers and print publishers and others only in artist-made impressions - wanting the subtle effects of the hand of the maker in there at all stages. I incline to the latter, but to be fair, professional printers do their jobs well and work hard to establish reputations and drive up the value and distribution of what they produce. I love seeing restrikes from the old preserved plates of Goya or Rembrandt and feel cheated by fools who cancel their plates in the mistaken notion that one must or that it is expected or that it raises the value of the prints. When an excellent craftsman has babied along that old washed-out, abused plate and done their best to pull out every bit of nuance left in there after the centuries, it is pure magic to see what can be midwifed into existence from an unpromising-looking piece of scrap metal. A fine printer can indeed feather the ink in and out of what’s left of a plate with rounded edges on all lines and little left to hold it; masterfully baby the paper into a receptive state that is something to behold and squeeze out yet another set of restrikes that really aren’t half bad. The choice isn’t about having perfect impressions after centuries of use and abuse, but of getting anything at all from the hand of the master once all the originals are in museums and otherwise unavailable. I’ll take a print from the thirtieth of the recorded editions of restrikes taken off a badly stored and somewhat corroded Goya plate, thank-you.

Who prints a plate can make a larger difference than you’d think - attitudes, aesthetic preferences, what liberties they dare take, what conventions they are bound by and finally those pedestrian attributes of experience and skill. My occasional printer Jonathan Clemens used to rib me mercilessly about undocumented proofs floating around somewhere in the marketplace and how you should only print what’s actually in the plate and not this airy-fairy selective wiping and drawing on the plate with fingers and Q-0tips. I – of course, gave it back to him about wanting to remove all creativity from printmaking as if it weren’t even art. I have also used the services of a printer in Prague - The Dřímal brothers (meaning reverie in Czech), a third generation of printers to the artists of Prague, living at an address called u Lesíčka (by the woods) but of course near a tram stop in downtown Prague. They liked to steel-face everything and they pulled amazing mass editions on a lower order cheap paper, meeting a punishing schedule and their impressions varied not an iota from beginning to end. Disciplinarians doing exquisite work with a craft I couldn’t begin to approach and doing so in a filthy, cluttered little walk up fourth floor flat - my stuff in a hodgepodge there with Jiří Anderle, Oldřich Kulhanek and whoever else they were printing at the time. The world holds such treasures in unlikely places - often just plainspoken people who hardly realize they are among the last caretakers of ancient skills and knowledge .

Not all printers are equal nor is every artist good at this side of his calling. I prefer using the services of a printer for lithographs, though I pride myself on being a better printer of etchings than most contract printers - at least when it comes to my own plates.

Three impressions of a Loon plate

Yet more printing didactica:

Colored printing usually means several plates and precise registration but it can also be done through rolling up colors on the surface of the plate over the normally inked intaglio image (Intaglio means within the depths of the etched lines). In this case one needs to keep the colors from bleeding into one another too much and muddying it all up and that is best done by modifying the viscosity of the inks, so they they become mutually repellant to one another. This approach allows me to create all manner of effects in the initial wiping of the plate and then to introduce atmospheric effects with the surface roll. It would be hard to be particularly consistent but fortunately, I am not all that interested in consistency. Offset does that far better than I.

Two lithographs - A two-pass print of Prairie Chickens to the left done on grained aluminum plates and a far more substantial and perhaps less delicately drawn print of a Pheasant done on a limestone of about 300 pounds to the right.

Above there are two game birds printed lithographically - something I only do occasionally, but which represents quite a remarkable way of working – either on several-hundred pound chunks of limestone or on grained aluminum plates. (Click the archaeopteryx below and you’ll be linked to others on the upland game bird page). Those sensuous blue-gray limestones come from the old Solnhofen quarry in Bavaria, lying in triangle between Regensburg, Munich and Nürnberg and though many other locations generate lithographic quality limestone, none are the equals of those from that first Solnhofen quarry. Here they found the very first Archaeopteryx – proof that birds and reptiles share a common ancestry. It was also here that Alois Senefelder first observed that albumen does strange things when an egg is broken onto limestone pavers under the strongly denaturing regime of the mid-day summer sun. The semi-porous stone, treated with the right chemistry becomes attractive or resistant to oil and water - which, as we all know, do not mix. Lithography (pictures from stone) - is premised on the chemical stabilization of a grease-based drawing on a very flat, evenly grained stone. When developed just right, the greasy drawing will accept grease-based ink and the non-image molecules of the stone will retain water and thus remain wet enough all through the printing process to repel the greasy inks. Simple principle, but it takes some doing to establish and make happen predictably. Lithography has seen many technical improvements since Senefelder’s brain storm in 1805 which have served us well in making the process faster, cheaper and more convenient, but nothing out there makes a more beautiful image that a good hand printer with a flat-bed offset, working from massive blue-gray Bavarian stones. Recall the gorgeous multi-colored theater posters and French bicycle advertisements by Alfonse Mucha and try to convince yourself that a modern day poster on a web press in any way supersedes them or makes them moribund. And this my friends is the basis of most modern printing technology - at least it was until the advent of ink jets and laser printers. We who grain those ancient rocks and draw upon them in grease-pencil, all periodically encounter bits and pieces of Jurassic era fossils - which we marvel over and then move along, casually sacrificing these relics for art.

We also have discouraging encounters with the limits of our own skills and have many opportunities to examine our own failings as beautiful drawings done over days and weeks in litho crayons and touche washes begin progressively to fill in and turn crude and ugly - or gradually fade away. Lithography is a jealous and demanding mistress. Each stone is different. Minor fluctuations in ambient humidity or barometric pressure result in changes in the ways that inks and the many varied pigments within them respond to the process - and then there are driers and retardants and varnishes and all the rest. Those of us who do not do this every day are often well advised to pay a contract printer who has spent years evolving those skills to do the roll up and etches on a finicky stone and get the perfect inking every time rather than keep losing images to the printers imps inhabiting nearly every workshop and pressroom. Laugh if you must, those of you who haven’t encountered these malicious little creatures.

My choice in printers was Jonanthan Clemens. He was an exemplary printer and even occasional print publisher. I worked with him over the course of thirty-some years, producing several dozen prints and his death gives me pause to reflect on that collaborative process.

Jon has unfortunately, passed over into that good night with hardly a moment to rage against the dying of the light, while being T-boned at an intersection by a drunken babe. The news-media only recorded him as an unfortunate impediment in the way of a cute and pregnant young mother who sent his silly & useless obstructionist corpse flying off into a corn field before dying. I only found out some weeks afterwards when asked by his step-daughter, Vanessa Thun, to come to the studio and discuss with her the disposition of all the artwork and many tons of printing machinery he’d accumulated. I brought along my trusty side-kick of a printmaker friend, Sniedze Rungis, who’d occasionally printed with Jon, and it was good I brought along that backup, for strength in numbers was appropriate on that day. Cracking the door and peaking in was to partake of an otherworldly apparition – like happening upon a foundering vessel, floating directionless at sea and boarding a Flying Dutchman.

Nobody about, but still, one didn’t feel alone in there. Had Jon not quit smoking several years earlier, there’d have certainly been a smoking pipe and steaming cup of tea left standing on the table, with perhaps a captain’s log open to the last entry - a half drained glass of rum.... There were spatulas of mixed up inks on the slab with brayers charged up and ready to be rolled onto the stones – as if he’d just stepped out for a smoke or to grab a cuppa coffee. You naturally looked around and expected Jon to be right behind you, coming in from the garden or down on the floor under a table plugging in an electrical plug – or worse – strange feelings. Be respectful you say to yourself - don’t get nailed snooping around or touching the unprocessed stone and leaving a tell-tale fingerprint - wouldn’t do at all...no siree.....

Jon did do some things in his lifetime other than getting in the way of a pregnant lady in her cups and in too big a hurry to be someplace more important – and he did them exceedingly well. Thus the passing of Jon Clemens gives me pause to reflect on the passage of every truly skillful master.

Highly skilled callings that rely upon apprenticeships and knowledge of physical materials as well as the work of a practiced hand - these are all facing increasingly rough times. Society seems to assume that the information will always be available on the web - that mere availability is sufficient. Skills such as ours, however, evolve and must be kept vital as living, breathing practices. These kinds of callings - with one foot planted firmly in the physical material world and the other in the past, among all the masters upon whose shoulders we stand – they all rely upon a knowledge that has become second nature by virtue of having been internalized through continual practice. Our skills are earned by embracing the mantle of ownership and caring for them as living beings. Otherwise the skills go dormant and cease to evolve.

Skills unpracticed become like a language left untended - one that you cannot fully practice and play with among fellow native speakers - among those who truly love and enjoy the intricacies and unique peculiarities of that particular and expressive grammar, the manifold implied secondary meanings and literary precedent inhering in any language. Lack of intellectual play and creative banter allow these minority languages to slip from daily use, such as buying gas or grumbling about the clutter. Instead of a useful part of life, they become something less or all too much - insufferably more - an all too serious ceremonial mumbo-jumbo steeped in protocol and honorifics, becoming stodgy in their unchanging untouchable humorless stature as they descend to slipshod use at much diminished levels (as they must if they are to survive at all and somehow include the shaky speakers with limited usage at their command). And there we are trying to maintain some semblance of balance as we descend that long slippery slope into barely used and dying museum pieces.

Languages, trades and skills die a little more irrevocably with each passing master - each one taking some small portion of that collective heritage to the grave with them. And indeed what is the point of learning Ojibway if you have nobody with whom to speak. What sadness inheres in having been Ishi, the last living member of the California Yanni, hunted to extinction by hateful settlers incapable of perceiving their humanity and in his lonely howl-at-the-moon sadness filled with a pregnant knowledge of not just nature and things to be named, but so much more. Filled to the brimming tearful edge of inexpressible sadness with all that can be said with a full language there upon his lips, if only there were a listener capable of understanding, Ishi stumbled out of the forest and onto a road in 1911, ready to give himself up to the lynch mobs - done with life and willing to embrace oblivion. He found to his amazement that he’d stayed out of their line of sight long enough to have outlived the lynch mobs. He was held in prison for want of any better way of keeping him safe until an anthropologist from the big city could come out and collect him. The sheriff didn’t quite know what to do with this last last wild Indian but assumed a professor might.

Alfred Kroeber, was a German anthropologist and became Ishi’s last friend. He studied the version of Yanni that Ishi spoke and wrote down what he could in his learned tomes about the soon to be extinct, Yanni Indians. He was well meaning, intelligent, sympathetic, friendly and yet so much can be said with a turn of context or sleight of grammar that he would always be an uncomprehending foreigner. Languages smell of where they’ve been and who has used them - who once gummed those very words in toothless reminiscences of times long gone and in what context. When there’s nobody left with whom to discuss what matters or with whom to let rip and really play with words - what remains? In a smaller way it is the sadness you’ll sense behind the superficial successes of every immigrant – of every elderly craftsmen whose children disdain the work done by hand and at the cost of the sweat upon one’s brow.

How must it have been when the last surviving indigenous inhabitants of East Germany, the Polabs were being contacted by Jesuit linguists interested in recording their noble savagery and recording a few stanzas of some bawdy drinking songs by which to remember their dying race? These ‘Last Mohicans’ had the complete patrimony of a culture scattered about the synapses of their brains with nobody but an uncomprehending linguist from the enemy encampment interested in hearing the slightest, most trivial aspect of it all? ‘We used to raid viking villages when they were off pillaging Normandy.’. .’We decline our verbs with some extra intermediate tenses’. ’We have lots of Gods, as you say about us. They are of course all aspects of the one and subsumed in the great numinous one-ness of it all, but what would be the point of trying to explain anything so subtle to your kind?’. And by 1725 they were gone like so many other smaller nations, devoured by more successful and better militarized nation-states with efficient tax collections and conscription - their people transformed magically into cannon fodder for somebody else’s dreams of grandeur in fields of battle nearby doing a number on the next loser in that endless race to the bottom.

And then there are the crafts and trades - the stuff we pass on mostly by watching another do it: Do as I do, more than I say....and we get back again to Jonathan Clemens and lithography.

Our grandfathers slowly winked out one by one and took with them the knowledge of fixing horse harnesses and plowing with oxen - perhaps the sensitivity for soil that will give Kohlrabi what it needs to thrive, rather than just make woody knots that nobody really enjoys. My father-in-law was among the last apprentices to an ancient and proud lineage of wheelwrights - people who knew how to construct and balance a wooden wheel - knew which exact tree to select from which elevation and side of the mountain and not just which species of wood from a lumberyard. The right wood was required to give the flexion and resilience required to withstand the torsion generated within revolving spokes carrying a load. The hub and braking mechanisms have very different physical requirements as do the outer rims. I handle my papers with that self-same intimacy. Jon Clemens knew his inks and limestone as well as his varnishes and what drying qualities he might expect of various pigments. We talked about that and swapped stories – keeping it all alive, but not for a museum or a kid with a recorder wanting to place it on This American Life or worse, but because it served a recognized and needed purpose. - made our lives better – made for beautifully sumptuous prints.

The subtlety of these things is great and the depth of knowledge within a trade or a craft is not conducive to casual surveying - not the stuff of Wikipedia overviews. I wonder sometimes if there is an ‘anything-wright’ to be found on-line? Perhaps a ‘software-wright’ - maybe a ‘punch-the-button for-your-tax-refund-cheque-wright?’ I suppose that’s unfair. The dead are inevitably forgotten in a few generations; folkways change; the clutter of moribund and now useless technology is unfailingly swept from the scene by fire, flood, invaders and vermin – remorselessly making way for the new. There is, however, something different about the passing of a master of stone lithography and etching. We are all painfully aware of how much has been lost already and what magnificent skills were wielded by 19th century engravers, chromo-lithographers, xylographers, book binders and oh so many others who could do by hand that which the machine really can’t do either and whose demise has more often led to reduced expenses with a commensurate lowering of the bar than it has to improved quality. Jon Clemens was such a bridge to the past in a society still in need of those living links more than it knows.

In Lord of the Flies, nobel laureate William Golding explored what an isolated society could become that has no memory of its past. It was a horrifying prospect of devolution to the common denominator of ignorant brutality and moreover a phenomenon whose indica-tors only a complete Pollyanna could possibly not see alarmingly on the ascendant. I once knew a professor who spoke of his students as consisting primarily of the militantly ignorant. That’s cold, but is there not some truth in it? I encounter plenty of the young and idealistic who think much the same of their own peers - don’t even trust them to vote at election time. Too busy - too self-involved- too cynical. The Good old days and people mooning about them used to be laughable and pathetic, yet today, we mostly envy the old-timers their good old days...Must have been nice....Coulda left us something too...

Jon was one who carried a disproportionate piece of that load of continuity with the past and did so in a discipline wracked with a pathological worship of the latest thing. (Try to enter artwork that's over two years old in an art show sometime). Jon printed for the long dead artists of the midwest as well as for his contemporaries. He knew them, had anecdotes, collected their work - understood their relationships to art history and saw past mere fashion in the arts to the substance inhering in truly fine prints of many generations. Thinking back to the prints in progress at Jon’s shop and handling plates and proofs, I recall him printing a great deal for Sidney Chafetz and Frank Stack in his last years, for several Japanese master printmakers visiting Western Michigan University - as well as major large multicolored, multi-plate pieces for David Driesbach - occasional work for Stephen Duren, Warrington Colescott.....even the great mid-American engraver Ray French and his dealer Thomas French Fine Arts. He came through Lakeside Studios under John Wilson and printed for many luminaries of the 60’s and 70‘s renaissance of printmaking who passed through Lakeside studio and Chicago’s Navy pier show - including the contemporary wood engraver, founder of Janus Press and McArthur award recipient Claire VanVliet. At Lakeside, Jon learned from master printers, until he too, slowly but surely, assumed that mantel himself.

I will remember Jon as a quiet modest man with a certain look in his eye that spoke of having experienced enough pain as to be unwilling to continue the cycle and be unkind to others. It reminds me of the the look one used to get from time to time in simple taylor shops or shoe repair stalls when a stooped and elderly man handed you back your shoes and the partly rolled up sleeve revealed a faded tattoo - a number. No self pity, nor much talk, just a good man whose tortured past is a closed book, but which summed to forming a profoundly decent and compassionate individual.

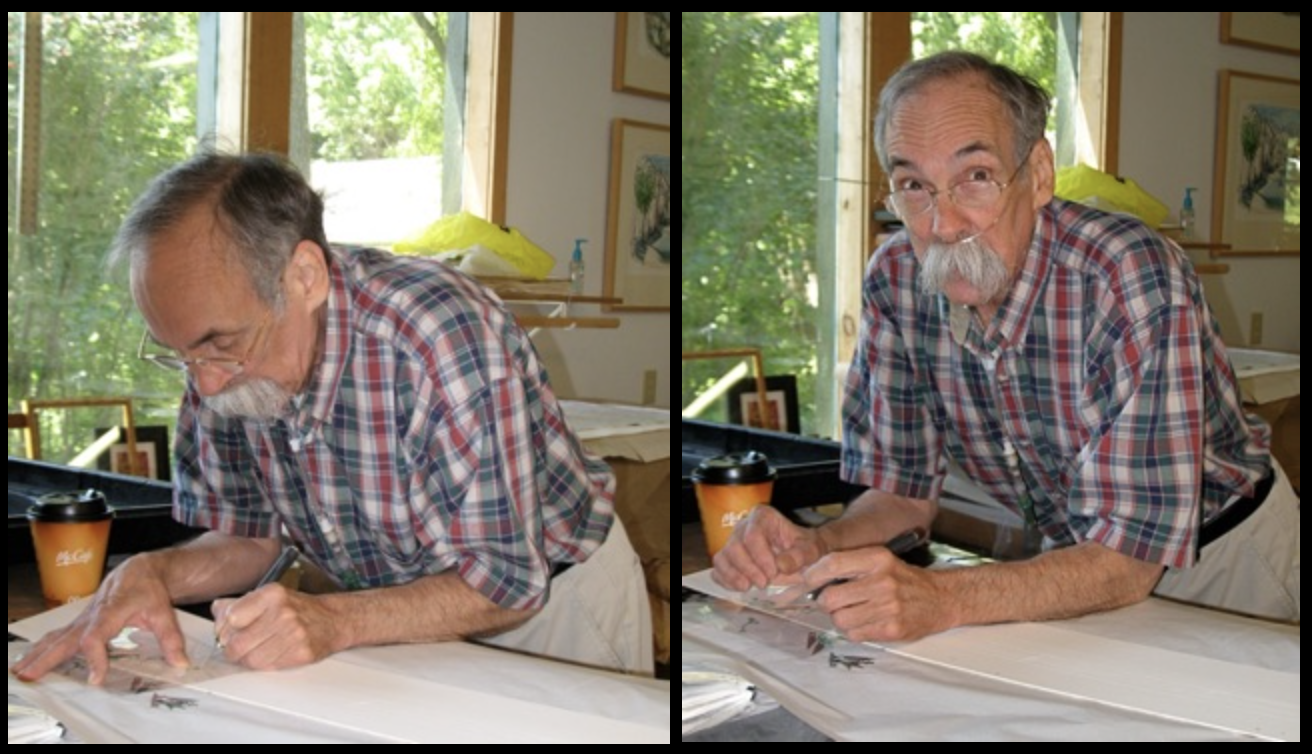

John Clemens in the studio just about to deliver some clever, pithy (dare I say pompous?) remark about the kinds of miscreants who would pee in their Gum Arabic solution to supplement the buffering capacity of the etchant or perhaps goose up a drypoint passage after the BAT (Bon a tirrer - meaning the good pull/ AKA final proof) has been delivered..... or perhaps just say Hi

Just the mustache ? – or did some great grand-pappy get around more than we know and confer a name in some strange concatenation of inexplicable events?

Multiple depictions of Jon Clemens done in that unforgettable way that every funeral parlor and class reunion seems to remember our loved ones – with generic pronouncements delivered in cadaverous tones that he was a uniquely creative person who will be missed. It makes me grateful I don’t have to do this for people I don’t know, whose interests I never shared. I will add that for members of the printmakers’ community in Kalamazoo, Jon was a founding member of the Southwest Michigan Printmakers in the mid-seventies.

There is of course a great deal more to be learned and said about all of this and there is curiously enough another section of this immodestly voluminous website where you can indeed indulge that curiosity.

Me in my older studio hard at work and you can click on that image to be taken to the much longer and more detailed and indeed long-winded view of making an etching in all its glorious details - going through all the laborious steps side by side with me as I turn a copper plate into luscious print on paper.

And here is a nice example of that exquisite touche wash we call ‘skin of the Toad’ - which is ssuch a signature of a good litho and which has to go down simply, fluidly, quickly and of course delicately and be etched and stabilized and brought up slowly and with sensitivity - just right – the mark of one who knows.

Art contests, Group & Theme Show – and Collaborations

Asked about art competitions, 6.83 artists out of seven will quickly cite the old saw that contests are for horses – but then again, we still have egos and want to be recognized, be a winner – perhaps even see some losers in our wake. We seem to continue to enter those frustrating and often idiotic art contests in spite of ourselves. In fits of denial and self-loathing, we repeatedly enter these silly shows and we moreover pay for the privilege of fighting with digital cameras and computers that tend to misrepresent art only to be ignominiously rejected by somebody’s brother-in-law asked to jury a show and take home a stipend paid for with our very entry fees. Many a local art center hardly even funds these shows, but counts on entry fees as a supplement to its budget. There are even shows whose prizes barely return the cost of entry and yet there we are, lining up at the door thinking it will help our reputations and visibility. Perhaps it does in some small way. We do want to participate in the scene, after all and be seen. I tend to resolve that conundrum by regarding this activity as my nod to the community I inhabit - a way of participating. Going much beyond Kalamazoo feels like trespassing on the territory of those who live there and participation brings little benefit to me or them.

Themed group shows are something else though and do not involve fees or prizes. They seem more honest affairs for participation among friends and colleagues in which my success is not your failure. Still, they are often troubling and hard to shoe-horn one’s self into and yet they are kinda Ok to go see. They do get us engaged enough get motivated to just get started on something - anything - and keep the chattering brain occupied while you make some good artwork. Here below is the result one such theme show and how I fit myself into its parameters. For you, I hope there is the re-enforcement of how seriously we take this matter of making art and meeting the demands of a commissioning patron – the many plates that never make the grade and what distress and effort lie hidden behind every nice piece of art well framed - elegant and there before you - seemingly effortless in its making by people whom you imagine to be uniquely gifted at birth with unreachable talents. We work pretty hard at developing these skills, keeping them sharp and there are all the failed attempts you will rarely see.

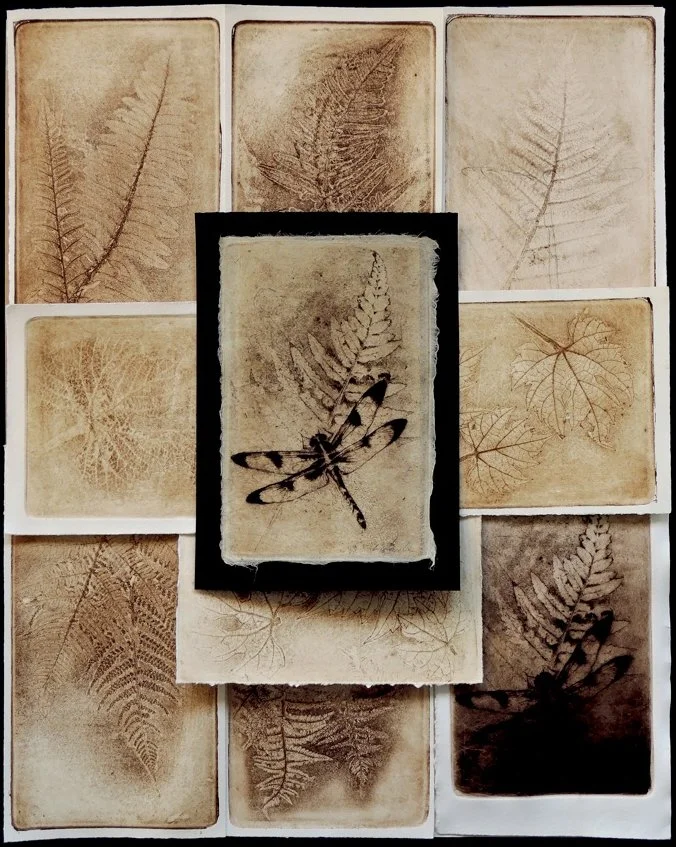

Vignoles Dragonfly (2016): One in Ten

Softground etching with drypoint – printed Chin Colle

4” x 6” inch plate size

Print unframed: $200.00

Framed tableau: $500.00

Ah, yes the many plates that never quite make the cut......the drawers full of also-rans....

Printmaking doesn’t actually come so easy as one might think and that’s worth a short rant on this page made for enhancing a collector’s understanding of the process; how we think,; how it happens; why we do what we do; why it all matters; collateral damage....

Now you may be logically wondering , what calling doesn’t have its difficulties? You do your studies, learn the trade, with all its oddities, dead-ends and technical pitfalls and then get on with making your images in that medium, right? No, no, no -– not so fast. It’s art after all and we can’t leave well enough alone - not the painters nor the ceramists and certainly not the printmakers. It’s all experimentation much of the time and nothing really works the way it should and most of us of course, are built for the new and innovative rather than finding a formula and starting a factory to turn out more of the same for the next three score and ten. Wouldn’t be art or much fun, would it now? And printmakers are technical sorts, who are after-all, an odd crossover between book publishers, printers, fine artists and often even writers – idea people, rushing in to embrace any failing technology that seems dated enough to escape being mere commerce. No siree; we gotta keep innovating and messing with the tried and true. So just like any agony and ecstasy chiseler, we do indeed, suffer for our art.

Here is my nod to all of that trial and tribulation on the press gang, assembled for an exhibition of printmakers entitled ‘TEN’. Ten fer pete’s sake. What do I do with that? Hang ten? The only thing that came to mind with the number ten that seemed worth my playing with was the point of decimation - the old military model of the Roman empire embraced by petty tyrants and brutal dictators everywhere. If a troubling population isn’t on-board with being invaded, taxed, conscripted, censored or brutalized - one in ten gets it in the neck. Then another one in ten a bit later, until order - well maybe the new improved version of order – is indeed instilled. With print-making, it’s more like one in ten that survives the cull. Here are nine false starts – plus the one that I deigned to call good.

The great thing about etching is that you have a plate and you can print it to see what’s there pretty well anytime in the process. If you aren’t satisfied, you can work some more and take a staggering profusion of intermediate proofs until you do indeed, eventually arrive at perfection. The down side is that you can indeed do this very thing and be stuck eternally noodling and improving something that has not gotten any better for being overworked and losing all its spontaneity – and – at the cost of much sanding, scraping, polishing and occasional bouts of bursitis.

This was a commissioned piece – made as a wine label for our very own home town Lawton Ridge Winery. I got no directions to speak of – just. ‘ do me something really nice - something to put on a great little bottle of Vignoles’. And please relax – I too, knew nothing about Vignoles. It’s made from a late-fall harvest of hardy hybrid grapes – a lot like a Spätläse Riesling or an Eiswein. Only the best of the best grapes are used, slowly withering away as the summer turns to fall. Temperatures are dropping and sugars are being sequestered by the vine into those last rare grapes still clinging to their stems. For the vintner, it’s a nerve-wracking piece of brinkmanship and a waiting game as bunch-rot sets in and grapes steadily keep dropping off the vine – losing volume as they mature into a smaller and smaller harvest of the most valuable and delectable of viniferous grapes. When do you say enough and take what’s left - that might be just a bit better in a few days or might conversely get hit overnight by wind and hail and be a complete loss. I tried to elicit the feeling of a bountiful but fading Indian Summer – the last dragonfly resting on the last dying fern – in evocation of those diminishing melancholic moments in the sunshine with their alarmingly shortening day-lengths and lengthening shadows.

As an artist commissioned by a friend, I didn’t want to disappoint him and so I found myself trying every variation that occurred to me, hoping to arrive at some desirable graphic expression for which I’d need feel no shame. Here you see how that looks, when grape leaves and hop leaves and ferns get etched into copper plates in anticipation of making this be all it can be. None of them are all that bad – and yet it is just the one in ten that actually sings and feels worthy of being fully developed and presented. Then my friend, the vintner screwed up his eyes a bit and just wasn’t so sure about what the Dragonfly says about his wine and how it fit with a Vignoles in particular. I knew the image was good and I knew my galleries would sell it just fine, yet doubts set in, while I held out and let Dean live with it for a while. The artwork in his hands did indeed do its insidious work on his mind – until he came around and decided it was indeed a keeper. Took a while, though. More on that and the vintner by clicking on the image and traversing down the wine and Mead labels page......

So how about edition numbers and proofs and documentation and what is valuable and valid and all that stuff they tell you in a gallery specializing in Published Prints?

Art my friends – standing uncomfortably in contrast to commerce in art. The supposition is that art is not enough – that the marketplace in art must be manipulated, regulated, sets of arbitrary rules imposed – hopefully creating a surfeit of product alongside the impression that is is rare by virtue of strict rules and ethics imposed upon its production and regulation and documentation. Its growth in value is ostensibly being guaranteed by those who are selling you the products. A typical dealer in Laser prints, Giclees, or offset reproductions are above all else well schooled in market trends and graphs demonstrating the investment value and growth of these products - which of course they may themselves be buying at auction through shils to establish a higher ‘market price. ‘ Suppliers of these goods are experts in obscuring the difference between original prints made by hand and all others. Modern day art departments are filled with those who love to posit the question and push the envelope as to what is and isn’t art and on it goes. It’s all a quaking bog out there if you want to be too sure of anything. The truth is that it’s hard to be sure. The work is beautiful or it isn’t. You’re being pressured by some marketers or you are talking to somebody who loves art and what they do and who seem real. You are thrown to your own resources and can only trust your won experience.

There’s a certain logic in limiting production and driving value of a commodity up with rarity, but with 8 billion people on the earth and 330 million just in the USA, it is hard to imagine that anything from our world of art will be a devalued commodity unless its production is driven by modern day printing technology and distribution systems and advertising. Anything made by an actual human being by hand is going to be done in numbers that approximate one or two pieces per country in the UN and not one in every town or household.

A painting or a drawing are a singularity - just one out there and clearly a potentially valuable commodity for that reason only. Then again a crumby drawing by Harvey Schlubgob is of much less interest to me than a fine Rembrandt etching no matter how many were printed by him in his lifetime or by owners of the plates after his death. A print that somebody messed with and kept changing and drawing on – or folding and printing on the back of is much like that as well and interesting for being the mark of creativity from an inquisitive person exploring the possibilities rather than an unprofessional standard that can’t get it right and do it the same every time. It’s an artist at work rather than an industrial product.

Today I am finding fewer and fewer artists bothering with editions and not just because nobody wants their work, but because they can’t second guess the market so They just print what they ned from the plate - perhaps numbering them in some kind of sequence or not. I seem to be of a generation that tried to do it right - like they taught us at school and found I couldn’t quite pull it off but that nobody really cares anyway. I still limp along and wonder why - while younger print makers seem to be even less enamored of that curious piece of old time marketing begin in Whistler’s day.

As an artist I need to make a living, and that is no mean feat. Each sale is small victory - a spitting in the face of the implacable modern day economy and the general feeling that money talks and bullshit walks. I gotta turn a buck, and not alienate those who want to believe in what I do and so there is a feeling of wanting to be honest about it and follow some ethical standard but also not hem myself in with rules that seem pretty arbitrary and not of my own making. Money is important but it’s still secondary to having time to make my art and so of course I bend over backwards to accommodate people who hold out the promise of crossing my palm with gold.

The rules of art hold higher primacy in my heart than do the rules of commerce. and that’s what I’ll tell anybody who wants to listen. Your giving me money is a lot less about a fair exchange in a market-driven sense, than a fair exchange in a human sense. I must live from something and if you value what I do, you should help me get by. Poor people and young couples and students should have nice things too, while rich people have more with which to be generous to the artist. Art has always been subsidized by those of means and taste and it is appropriate that it should be so.

If I get asked for number 22 of the edition and then another collector wants numbers 17 and 33, I say yes and bless your heart. Then somebody else wants to consign numbers 10 -20 and so I send them on, but the cat pees on one and so I destroy it and reprint it for that old friend who should know better but runs a nice gallery and I do owe her some favors. Then you run out of prints and you open the plate to start printing another few prints from 35/100 to 50/100 and try to remember which ones left the studio and where the numbering needs to begin again and where the gaps are and by the time you’re halfway into the edition, one’s numbering ( or at least mine) is hopelessly confused and everything becomes an artist’s proof because that’s all you know to do any more. Rather than poor business or accounting practices or unprofessional activity, I would maintain that this is the only stuff that’s real and a sign of having the real thing in hand rather than just some marketer’s scheme to make money on a currently popular artist. It is made by hand by one person and thus in the context of the world cannot be a devalued to the level of commercially manufactured product – there being no more than one or two per country in the UN, because we can’t do that much standing at the press and get anything else done. While the publisher can hire people and machines and do all else and assure you of much, it’s his word and not much else you have to go on - while the economies of scale are not to be thought away.

A print publisher will print an edition of 10,000 on some Giclee machine or Offset or laser printer or even have the artists drawing made into a plate and printed in ways that are hybridized artist/commercial printing technologies and document it and even call some of these impressions artist’s proofs for some strange reason and strictly limit them to 12 percent of the edition and then mark them up as a rare extra valuable product. They will then film themselves destroying all imperfect impressions , the over-runs and false starts and it just seems so professional and beyond reproach that you feel cowed into accepting it as a norm. Oh so much verbiage and so many banks behind it – ISB numbers and copyrights registered with the central bureau of tomfoolery with writs of habeus corpus and cease and desist orders kept current an warm in the judges chambers to keep it all up and running – but it’s also cold. You as a collector though, should love nothing better than finding a stash of ratty looking proofs in which the artist worked out his composition and tried a few bad ideas before adding the great stuff and then went off in some direction and rolled it all up and stuck it in a corner for a decade or a century. A friend of mine ended up with a teensy little drawing cut to pieces and glued up with chicken scratchings on it that was Picasso’s way of working out some compositional alternatives to the painting of Guernica. Without Guernica in the great grand museum and all the art history books, it wouldn’t be much, but now that the painting is famous, the sketch is an interesting piece of that puzzle with substantial art historical worth – to say nothing of pecuniary worth, way beyond any “strictly limited edition” of an offset reproduction of a Picasso. Of course this little picture is not in the catalogue raisonne and will probably never be recognized by the world as a Picasso because there are of course collectors and writers and museums all invested in the body of work having a beginning and an end and being the expert and so forth. The books are closed on Picasso unless of course they are not, but you have to bring in some real firepower to fight that moloch. My buddy was in Spain when some old colleague of Picasso died and the family sold off the estate and he bought a lot of pictures from about the right time period - The man knew Picasso and might have been given some silly little scrap in a bar or stolen it or something in between. It could be a forgery but why let it go that way and not capiltalize on it? I look at it and know instantly that this is the way we all work when it’s just for us and wondering what this might do for the balance or composition. Right as rain and probably never pass the legal tests.

So then like many an artist I have a studio back room brimming over with scraps and false starts and ideas that underlie the finished works you can see in my catalogs or in my website. They are often cool and also flawed - one plate overprinted onto another with some chalk drawings over it all - too interesting to toss and too tattered - or dirty -looking to display or sell. I tend to throw away little and could find rolls of proofs and sketches for most of my etchings somewhere in some dark corner and in secret hope a museum curator will some day see them as the gold that underlies the process of creation and that this junk pile will be my Social Security fund some day – since the real one is pretty stingy with the self-employed. . The best proofs got reused or often the most interesting but deeply flawed ones do – for there is a liberation in already ruined materials that leave no sense of pressure like the perfectly stretched new pristine canvas upon whose flawless surface nobody dares inscribe that first fatal scrawl. Like buying a new car and just giving it that first scratch or dent yourself right then and be done with it. Used recycled materials carry a certain liberation within their flawed structures.

The difference really here is that the publishers offer a commercial deal and some sense of security backed with advertising and publicity. Its real and I don’t wish to denigrate it. Having Goya or Audubon prints in hand is wonderful and they do appreciate with time. The assurances that they are “strictly limited” are a bit hollow though. Goya’s plates have been reprinted dozens of times in restrike editions until they are but ghosts of their former glory. I am glad they do this because the primary horse before the cart is that beautiful art be available and that I too could have a Goya if I were so inclined. That is more important than marketing integrity by a long shot. That is placing artistic integrity and honesty before fiduciary obligations.

Then again Dali prints are the opposite – strictly limited to an edition of 2,000 in Europe with an Australian edition and then a North American edition and a special edition for the bicentennial of independence of the island nation of Samoa and so it goes. French police detained truckloads of empty artist papers in the tens of thousands on skids, each with a Dali signature on it and no image, going somewhere for some purpose and avoiding some taxman. In the USA we have various artists who never actually make anything original or who occasionally do but who’s complete marketing is for Giclee reproductions and whose point is to confuse the line between reproduction and original print. They have Ponzi schemes for the distribution of these works and especially the dealerships in these specious “works of art” and sell them through machinations of marketing schemes that stress appreciation of investments above all else and are as spurious as any other pyramidal sales scheme. Their promises are worthless and museums refuse to accept the works as gifts because curating and storage of worthless objects still costs them money.

Like many another artist, a print is for me quite often the basis of a further drawing – especially an incomplete print a proof or one with flaws – throw a monotint over it, toss it into a vat of coffee – draw something more on it – evolve new ideas that may become another state of the plate or not - or give it to my bees and let them build honeycomb upon it. Hard to describe all that at some point, but if I let it out of the studio, I sign and date it. They are mostly not editions at that point but just one of a kind – something real and of worth but hard to describe sometimes. Innovative things don’t often fit neat categories. Commercial products tend to scrupulously do so - enough so to withstand legal challenges and fiduciary scrutiny and attacks by those selling a stock short and even nattily dressed currency speculators arriving with bodyguards driven in fancy sports cars with armor plating. So then, which category of folks do you want to open your doors to, invite in to meet your family and have a glass of wine with?